President Joe Biden’s approval rating is the lowest it’s ever been. According to recent Gallup polls, Biden’s current job approval rating is 42 percent, down from 57 percent at the beginning of his presidency. Biden’s current approval rating is lower than every other president Gallup has asked about at this point in their presidency — besides former President Donald Trump, who had just a 37 percent approval rating at around the same time in his presidency. The most dramatic difference between Biden and a past president is between him and former President George W. Bush — 301 days into their presidencies, Bush’s approval rating was 85 percent, particularly because at this time in 2001 the country was only a couple months removed from the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks.

Of course, these things tend to fluctuate, and only two former presidents — Dwight D. Eisenhower and John F. Kennedy — enjoyed net positive approval ratings throughout their entire presidencies.

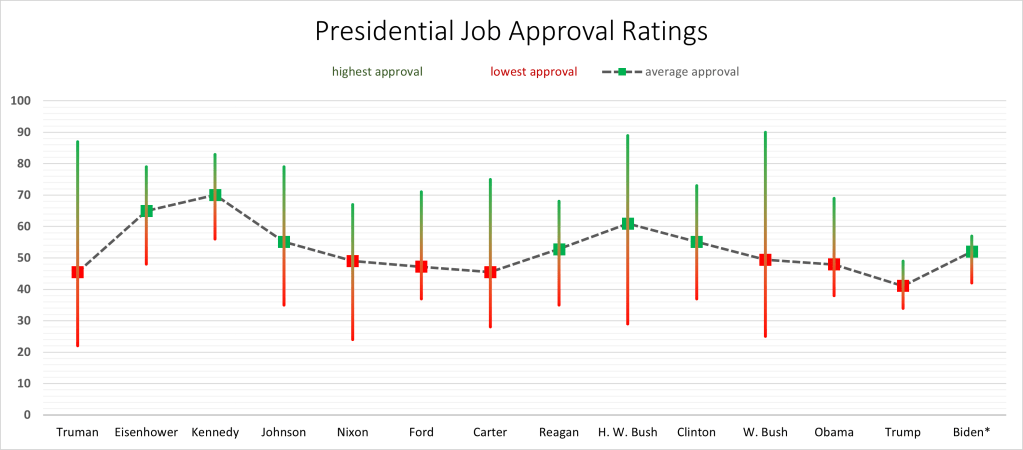

This chart is a comparison of the 14 most recent presidents and their job approval ratings from throughout their presidencies, using the numbers from Gallup’s site.

If Biden is counted, half of the fourteen most recent presidents have had average approval ratings over 50 percent (including him), while the other half have had averages below 50 percent. There is a large difference between the highest and lowest approval ratings throughout the presidencies of both Bushes and Harry S. Truman, but the difference between Trump’s highest and lowest approval ratings is only 15 percentage points — the same number between Biden’s, as of now.

Of course, Biden is a different case, considering he hasn’t even been in office for an entire year yet, but it is interesting to see the variations in approval ratings over time among other presidents. Truman, for example, had very high approval ratings after the end of World War II, but they had dropped dramatically by the end of his presidency. Lyndon B. Johnson’s approval was on a downward slope for most of his time in office, while from the end of his first year onward, former President Barack Obama trended mostly around or just under 50 percent.

Four of these former presidents also lost their reelection bids, and all had approval ratings right before the elections in the 30s or low 40s — Gerald Ford, Jimmy Carter, George H. W. Bush, and Donald Trump. Obama and George W. Bush both had approval ratings just below 50 percent but still won their second terms, while Truman had an approval rating of just 39 percent right before the 1948 election, which he still managed to win. The 2024 election is still far ahead of us and there’s no certainty that Biden will (or won’t) seek another term, however, so it might be premature to talk about that now.

So, something that we can discuss now — when compared to past presidents, Biden’s job approval rating was low right after his inauguration, too. Gallup’s first poll after his election showed a 57 percent approval rating, which beats Trump again (44 percent) as well as Ronald Reagan and George H. W. Bush (51 percent each). The younger Bush’s initial approval ratings were tied with Biden’s, which means that the other nine presidents had higher first approval ratings after they took office (Truman, Johnson, and Ford weren’t elected, which might count for something).

What I find particularly interesting, however, is the percentage change between Biden’s post-inauguration approval and his approval now roughly 300 days in. The comparisons with former presidents aren’t perfect here, because the polls were taken at different points in their presidencies, but every president back to Truman (besides Johnson) has a rating from within about a month shy of 300 days in office. These numbers show that most presidents have a lower approval rating at these later times than just following their elections, but Biden still ranks among the top (or bottom, depending on how you look at it) here — his approval rating fell by 26 percent from his inauguration until now, which beats every former president besides Truman and Ford (both at 28 percent), who weren’t elected to their first terms anyway. The most dramatic increase is 54 percent for George W. Bush, again due to Sept. 11.

No poll is perfect, and there’s many other ways of gauging how a president is doing in office, but public opinion polls can be an interesting and valuable way of measuring what people think about the president’s job performance. Historical trends can show how our current president stacks up against those in the past and give us a metric to see how the public’s opinion on a particular president has changed over time.

Biden isn’t even a year into his presidency yet, so just about anything could happen in terms of what the American people think about him. Compared to past presidents, Biden’s approval rating is not the worst in just about any way you slice it, however, his falling ratings since January do show that he has lost some support since then.